CLARITY Act, Banks, and the Battle for Yield

The CLARITY Act has sparked a debate about the future of money and banking in the United States. A central provision would prohibit digital asset service providers, such as cryptocurrency exchanges, from paying yield to customers for merely holding “payment stablecoins.”

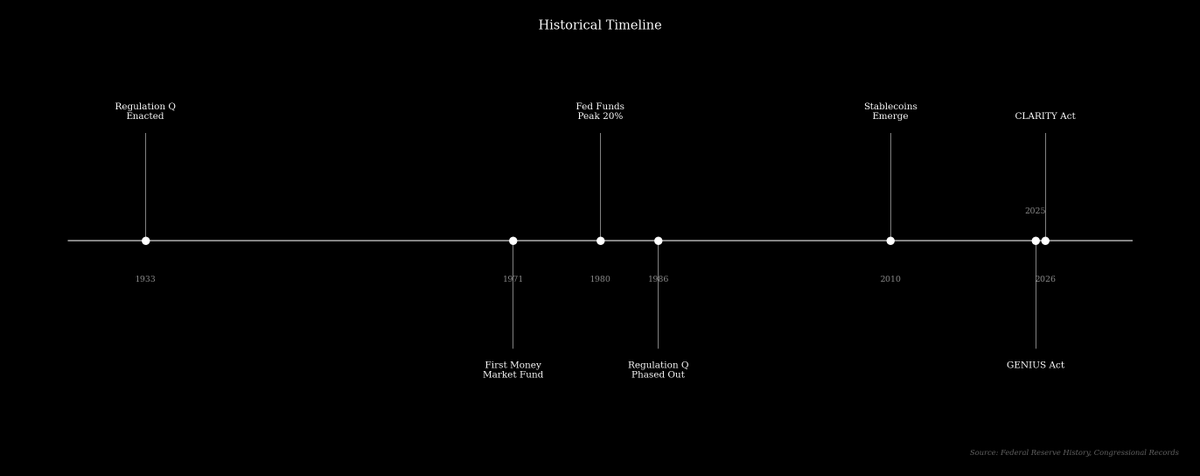

This proposed ban on third-party platforms follows the earlier GENIUS Act of 2025, which already prohibits the stablecoin issuers themselves from paying interest. The banking industry’s support for these measures is an attempt to protect their spread, which is a lucrative piece of their business model.

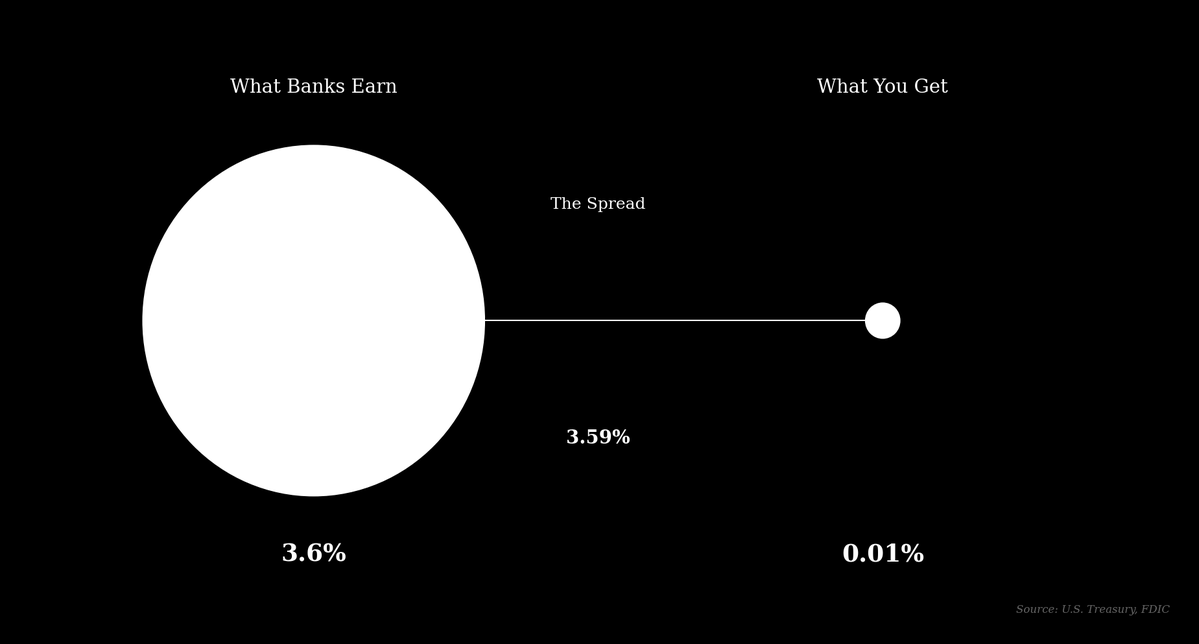

To simplify, banks operate on a model where they accept deposits from customers and pay a low rate of interest, then lend those deposits to others or invest them in assets like government bonds at a higher rate. The bank’s net interest margin, or spread, is the difference between the interest earned and the interest paid.

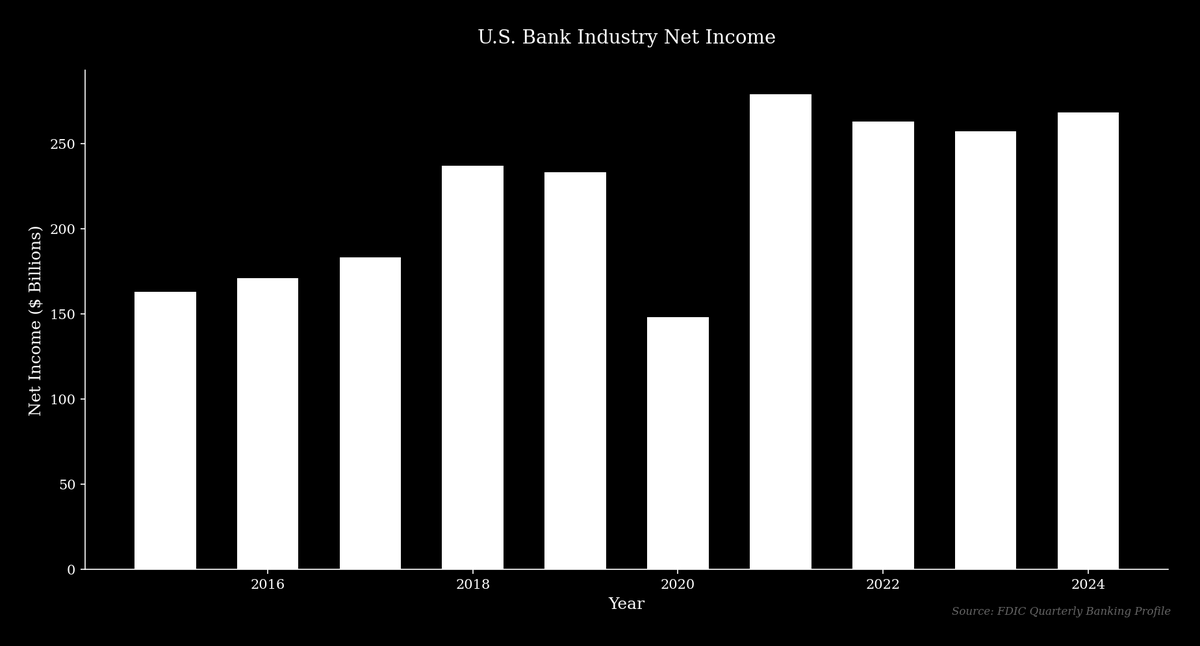

This model can be highly lucrative. In 2024, JPMorgan Chase reported a record net income of $58.5 billion on $180.6 billion in revenue, with its net interest income of $92.6 billion being a primary driver.

New fintech alternatives offer depositors a more direct path to higher yields, introducing a level of competition the industry has historically avoided. It is not surprising that some of the largest incumbent banks are using regulation to protect their business model, a strategy that makes sense and has historical precedent.

Bimodal Banking Sector

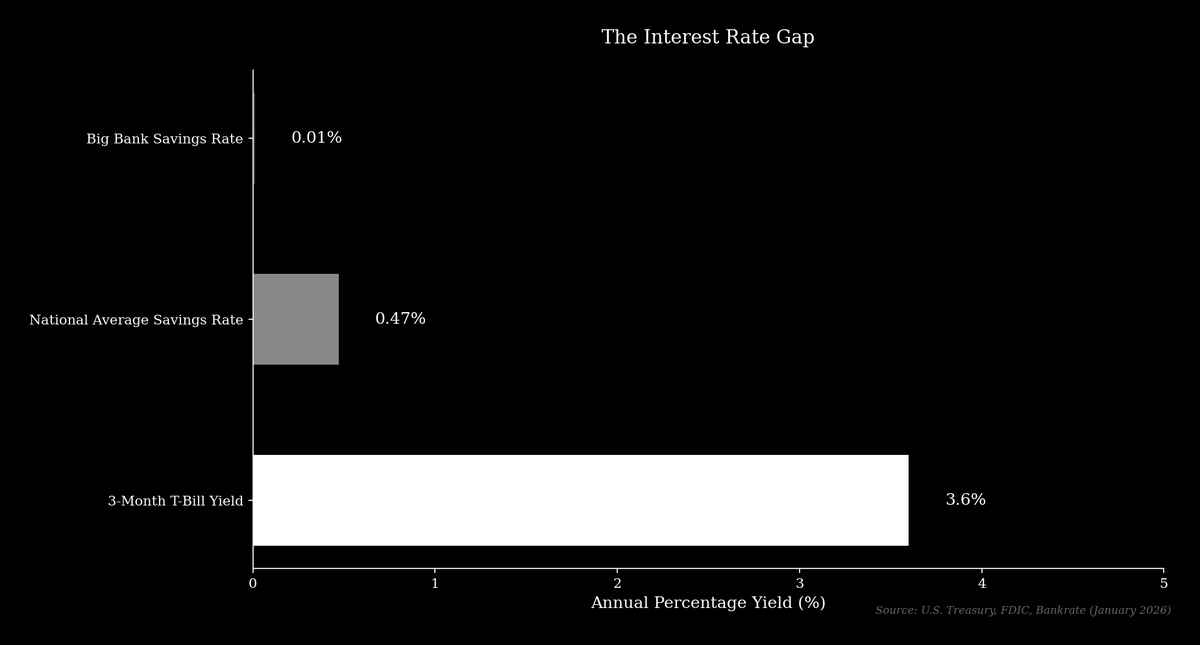

As of early 2026, the national average interest rate on a savings account is 0.47% APY, while the nation’s largest banks, including JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America, offer a standard rate of 0.01% APY on basic savings accounts. During the same period, the yield on a risk-free 3-month U.S. Treasury bill was approximately 3.6%. A large bank can therefore take a customer’s deposit, purchase a government bond, and capture a spread of over 3.5% with minimal risk.

With approximately $2.4 trillion in deposits, JPMorgan Chase could theoretically generate over $85 billion in revenue from this spread on its deposit base alone. While this is an oversimplification, the point still stands.

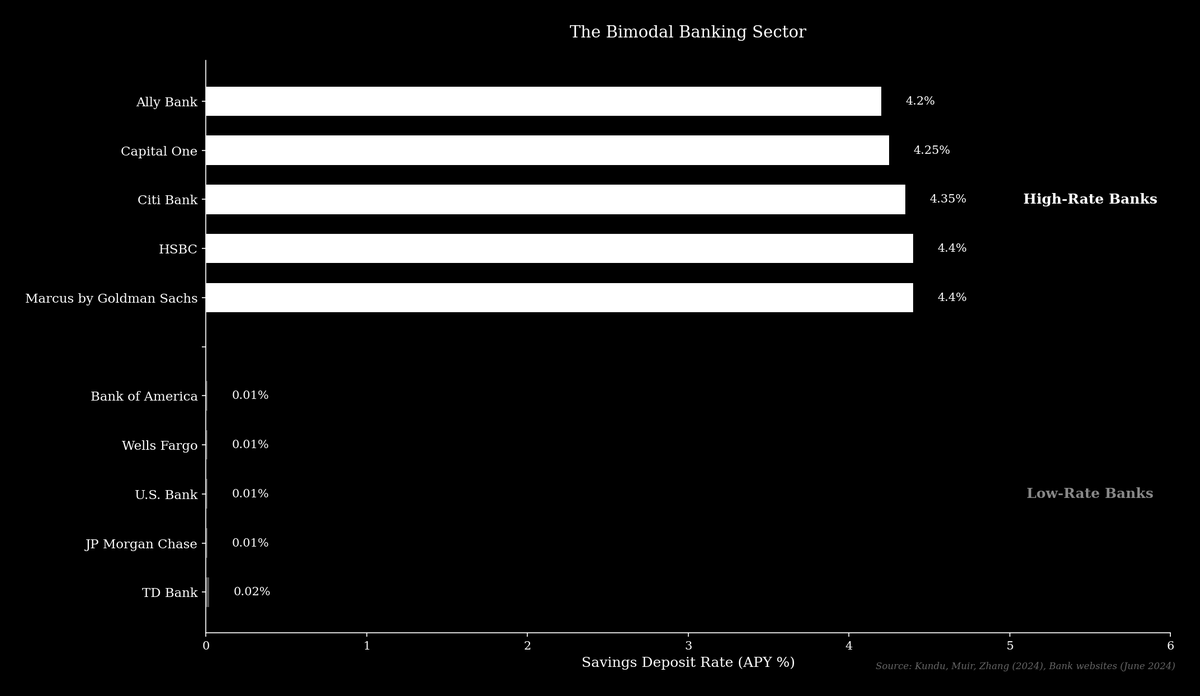

Since the Global Financial Crisis, the banking sector has split into two distinct types of institutions; low-rate and high-rate banks. Low-rate banks are the large incumbents that use their vast branch networks and brand recognition to hold deposits from rate-insensitive customers.

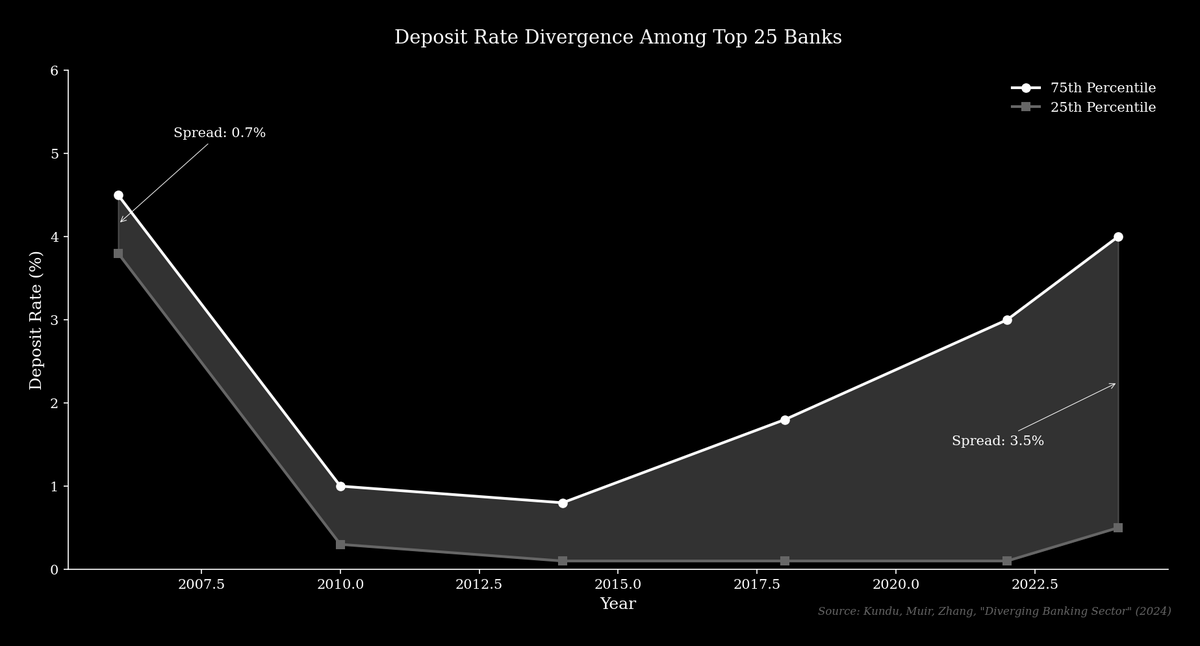

High-rate banks, such as Marcus by Goldman Sachs or Ally Bank, often operate online and compete on price by offering deposit rates closer to market rates. Research from Kundu, Muir, and Zhang shows that the spread between the 75th and 25th percentile of deposit rates among the top 25 banks widened from 0.70% in 2006 to over 3.5% today.

The business model of a low-rate bank is profitable because it relies on a depositor base that does not actively seek higher yields.

“$6 Trillion Deposit Flight”

Banking industry groups have argued that allowing yield on stablecoins would cause a “deposit flight” of up to $6.6 trillion, which they claim would drain credit from the economy. Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan articulated this concern at a January 2026 investor conference, warning that “deposits aren’t just plumbing, they are funding. If deposits move out of banks, lending capacity shrinks, and banks may have to rely more on wholesale funding, which comes at a cost.”

He added that Bank of America itself would be “fine,” but that smaller and midsize businesses would feel the impact first. This argument frames deposits flowing into stablecoins as being removed from the commercial banking system. However, that’s not always the case.

When a customer buys a stablecoin, the U.S. dollars are transferred to the stablecoin issuer, who holds them in reserve. For example, the reserves for USDC, a major stablecoin issued by Circle, are managed by BlackRock and held in a mix of cash and short-dated U.S. Treasuries. These assets remain within the traditional financial system, meaning the aggregate level of deposits does not necessarily change, but is simply reallocated from a customer’s account to the stablecoin issuer’s account.

The Real Issue?

The banking industry’s real concern is a flight of deposits from their own low-rate accounts to higher-yielding alternatives. Products like Coinbase’s USDC Rewards and DeFi products like Aave App offer yields that dwarf what most banks pay. For a customer, the choice is between earning 0.01% on a dollar at a large bank or over 4% on the same dollar held as a stablecoin, a difference of over 400 times.

This dynamic challenges the low-rate bank model by encouraging customers to move funds from transactional to interest-bearing accounts and by making depositors more rate-sensitive.

In a world with yield-bearing stablecoins, a customer could access market rates without switching their primary banking relationship, which would accelerate the existing competition between banks. As financial technology analyst Scott Johnsson notes, “banks really aren’t competing with stablecoins for deposits, they’re competing with each other. Stablecoins just accelerate that dynamic to the benefit of the consumer.”

The research from Kundu, Muir, and Zhang supports this view, finding that when market interest rates rise, deposits tend to migrate from low-rate banks to high-rate banks. This migration supports lending for personal and commercial loans, which high-rate banks increasingly originate, an effect that yield-bearing stablecoins would likely replicate, channeling capital toward more competitive institutions.

A Historical Parallel

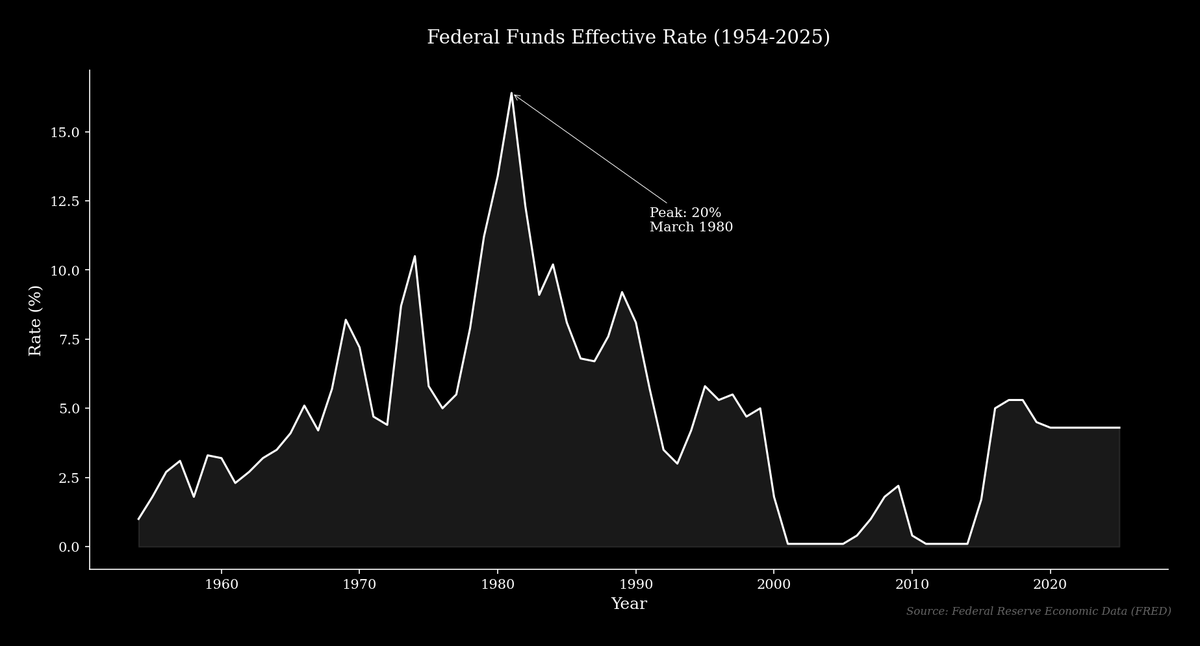

The current conflict over stablecoin yield is similar to the historical conflict over Regulation Q, a rule enacted during the Great Depression that limited the interest rates banks could pay on deposits to prevent “excessive competition.” For decades, the rule had little effect because market rates were below the legal caps, but by the 1970s, rising inflation and interest rates made the caps binding. The federal funds rate, which had been below 5% for most of the 1960s, rose dramatically, peaking at 20% in March 1980, while banks were legally prohibited from offering competitive rates.

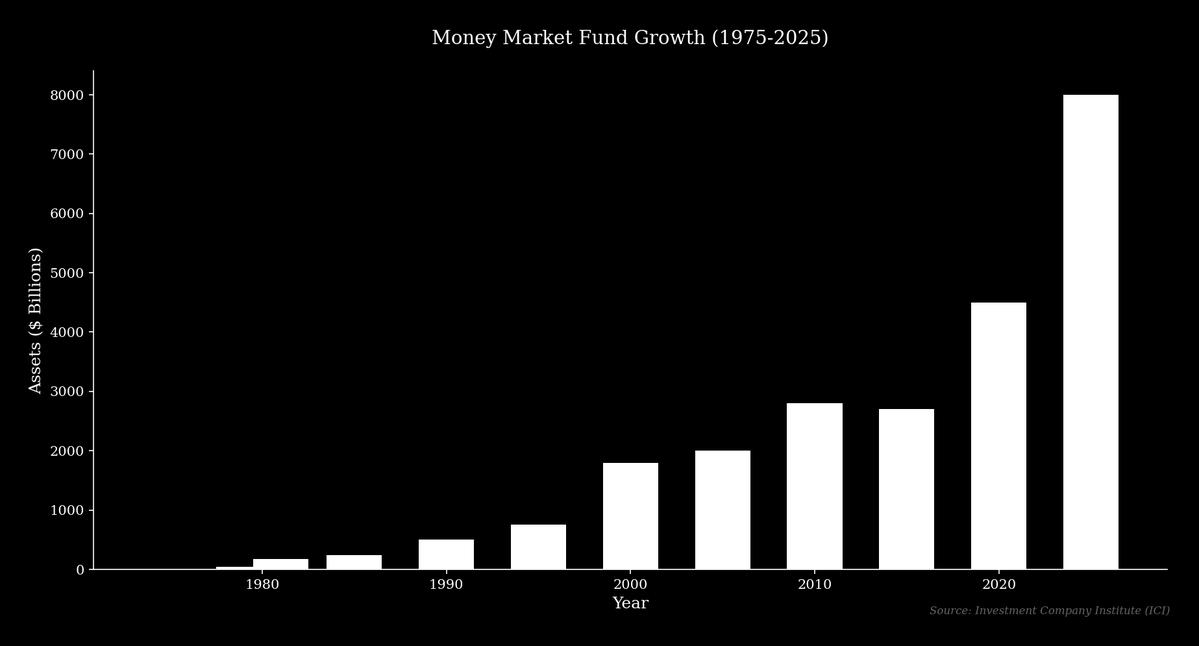

In 1971, Bruce Bent and Henry Brown created the first money market mutual fund, the Reserve Fund, which offered savers market-rate yields with check-writing features. Today, protocols like Aave serve a similar function, allowing users to earn yield on their deposits without a bank intermediary. These funds grew from 76 funds with $45 billion in assets in 1979 to 159 funds with over $180 billion just two years later, and today hold over $8 trillion.

Banks and regulators initially opposed this development. The rules were eventually seen as unfair to savers, leading Congress to pass legislation in 1980 and 1982 to phase out the interest rate ceilings.

Rise of Stablecoins

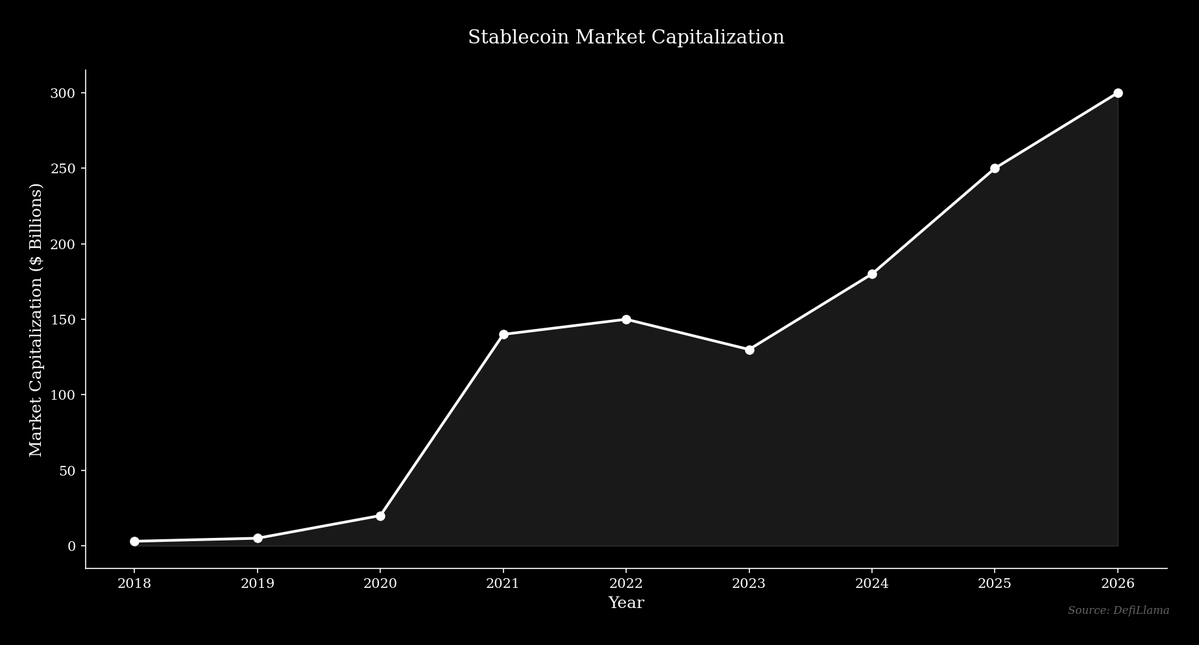

The stablecoin market has expanded at a similar pace, growing from a total market capitalization of just over $4 billion in early 2020 to over $300 billion by 2026. The largest stablecoin, Tether (USDT), crossed a market cap of $186 billion in 2026. This expansion indicates a demand for a digital dollar that can move freely and potentially earn a competitive yield.

The debate over stablecoin yields is the modern version of the debate over money market funds, where the banks lobbying against stablecoin yields are primarily the low-rate incumbents who benefit from the current system. Their objective is to protect their business model from a technology that offers more value to consumers.

The market tends to adopt a technology that provides a better solution over time, and the role of regulators is to decide whether to facilitate this transition or to delay it.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [0xKolten]. All copyrights belong to the original author [0xKolten]. If there are objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and they will handle it promptly.

- Liability Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute any investment advice.

- Translations of the article into other languages are done by the Gate Learn team. Unless mentioned, copying, distributing, or plagiarizing the translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

Gate Research: 2024 Cryptocurrency Market Review and 2025 Trend Forecast

Altseason 2025: Narrative Rotation and Capital Restructuring in an Atypical Bull Market

The Impact of Token Unlocking on Prices

Detailed Analysis of the FIT21 "Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act"

Gate Research: Web3 Industry Funding Report - November 2024